By Omar Eaton-Martínez, Assistant Division Chief, Historical Resources of the Maryland-National Capital Parks & Planning Commission

In 2032, President Kamala Harris established a task force to study the feasibility of creating a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) like the one established in 1995 to help South Africa heal from the damage inflicted by apartheid. This task force, led by then Senator Sanai Eaton-Martínez, issued a report that concluded that the United States has not fully dealt with the atrocities and long-term impact of the genocide of First Nation peoples, enslavement of Africans, and incongruent immigration policies toward non-white peoples.

Now, in the wake of the recent election, President-Elect Eaton-Martínez has announced that one of her first actions as POTUS will be to act on the recommendations of the report, creating a TRC that will enable Americans to come to terms with their past on a morally accepted basis and to advance the cause of reconciliation.

In her victory speech, which pundits have titled “Mea Culpa,” President-Elect Eaton-Martínez also acknowledged the role and responsibility that the American government has had in perpetuating systems of oppression. She apologized for the many barbarities, murders, and crimes against humanity that have been silenced by those in power. Her humility and repentance galvanized the American people as she modeled true servant leadership.

When the Equal Justice Initiative’s Memorial to Peace and Justice opened in Montgomery, Alabama, in 2018, it was the country’s first national memorial to victims of lynching.

Museums have played a significant role in the progress the United States has made in combatting oppression, and President-Elect Eaton-Martínez made it clear in her remarks that she sees America’s museums as crucial partners in this effort. Even a brief examination of the events of the last few decades shows how intertwined our field has been with the struggle to come to terms with the country’s history of racial oppression. We can find many individuals, groups, and organizations in our field whose work exemplifies how we can contribute to the hard work that is to come.

The TRC comes as an aftermath of centuries of unresolved oppression, which has privileged leaders who are too proud to apologize and who consider admitting culpability to be a sign of weakness. Consequently, we have seen social movements evolve from the Twittersphere like #BlackLivesMatter in 2013, #MuseumsRespondtoFerguson in 2014, and #MuseumsSoWhitein2016. The blogosphere also has produced provocative writings that critically analyze systems of oppression and how museum spaces perpetuated or rebuked them: sites like the Incluseum, Visitors of Color, Black Girls Museum Blog, Cabinet of Curiosities, and the Heritage Salon, to name just a few.

Initiatives in the museum sector, such as 2018’s Museum as Site for Social Action (MASS Action) toolkit, have prompted museums to reimagine their spaces as venues for communities to mobilize around human rights issues. During the same period, the work of social justice-centered mobile museums like Monica Montgomery’s Museum of Impact, the first of its kind, and the Justice Fleet empowered visitors to transform from bystanders to “upstanders” and fostered community healing through art, play, and dialogue. Finally, coalition building movements like Museums and Race and Museum Hue brought together professionals of color and white allies to challenge institutional policies and systems that perpetuate oppression in museums and to advocate for people of color in arts, culture, history, science, education, museums, and creative economy.

Another notable milestone in our progress toward redressing injustice came in 1989, when Bryan Stevenson founded the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). The organization is committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society. From its inception, one of the ways EJI has engaged in this work is through cultural projects that illuminate the history of slavery, lynching, and segregation. In 2013, EJI erected markers that documented the domestic slave trade in Montgomery, Alabama, and gave visibility to a devastating period in American history that too few people acknowledge or understand. Five years later, Stevenson opened the National Memorial to Peace and Justice (NMPJ) and the From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration Museum (FEMM) near Montgomery.

NMPJ was the first of many memorials in the United States dedicated to the racial terror of lynching, and it arose at a time when historians and artist were beginning to confront a number of suppressed histories. Vincent Valdez’s series of larger-than-life paintings titled The Strangest Fruit was inspired by the erased history of lynched Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the United States from the late 1800s well into the 1930s. That series, and the exhibitions and symposia organized around them in 2013 and 2014, unveiled white supremacy’s storied violence against Mexican Americans. Starting in 2020,many historical markers and memorials were established commemorating the Mexicans and Mexican Americans who were terrorized, persecuted, and lynched by angry whites in Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and California.

The rise of these types of memorials coincided with a growing movement to remove Confederate monuments. This period of challenging the American exceptionalist narrative is particularly remembered for the violence that occurred in Charlottesville, Virginia, on August 12, 2017. White supremacists protesting the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee were met by counter-demonstrators standing against hate. A woman named Heather Heyer was killed by a car driven into the crowd where she was standing in peaceful protest.

The fear, anger, and passion attached to Confederate monuments made them objects of power. Calls to remove flags, statues, and other such symbols from places of public honor were invariably accompanied by the suggestion that this power be constrained and rendered safe by consigning the memorials to museums. So, even as museums were helping to surface some stories and memories that had long been suppressed, they were entrusted with the task of contextualizing and detoxifying others.

Filmmaker, musician, and activist Bree Newsome is celebrated in art and popular culture for her bravery in scaling a flagpole to remove a Confederate flag from the South Carolina State House in 2015.

Museums have a long history of harnessing technologies in service of their missions. In 2014, the Center for Civil and Human Rights’ Human Rights Movement gallery, “Spark Of Conviction,” made notably effective use of interactive technology. When it opened in 2016, the Smithsonian’s own National Museum of African American History and Culture featured compelling video testimonials integrated into its history galleries. And FEMM’s impact on visitors through exhibitions and programs exploring the legacy of slavery, racial terrorism, segregation, and issues of mass incarceration, excessive punishment, and police violence was amplified by the fact that the museum launched just as virtual reality (VR) technology was beginning to mature. The museum used VR to immerse visitors in the sights and sounds of the domestic slave trade, racial terrorism, and the Jim Crow South. Over the past two decades, the museum’s visuals and data-rich exhibits have given millions of virtual visitors the opportunity to investigate America’s history of racial injustice.

In 2030, inspired by FEMM’s successful use of VR, a team of computer scientists named We Are Wakanda (WAW) developed an advanced immersive virtual technology to support a program They called “Take a Walk in My Shoes” ( TAWIMS). This now-familiar program allows the user to explore a virtual world as a person with a different ethno-racial, gender, or sexual orientation. As museums nationwide began to reorganize missions, visions, and governance to more evenly distribute power and privilege, WAW decided that TAWIMS would be most effectively deployed in museums. Now, TAWIMS installations are in least one museum per state and US territory, and the program’s impact has caught the attention of lawmakers, critical race scholars, and museum professionals all over the world. The experiences that TAWIMS produces have changed the lives of liberals, conservatives, and moderates, people from across the spectrum of political thought. It is WAW’s hope that these transformational experiences will provide a new context for the oppressed and the oppressor, fostering civil dialogue so that people can discuss differences, discover similarities, and tear down the wall of hostility built by greed and irrational fear.

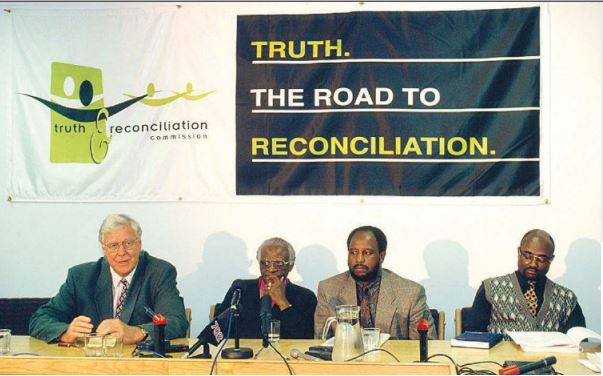

The restorative justice work of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, shown here circa 1996, served as an inspiration for the founders of the USTRC.

“In South Africa, you can’t go there without learning about the history of apartheid. In Rwanda, you cannot spend time there without being told about the legacy of the genocide. If you go to Germany today, in Berlin there are monuments and memorials and stones that mark the spaces where Jewish families were abducted … but in America, we don’t talk about slavery, we don’t talk about lynching, we don’t talk about segregation. So now, it’s time to talk about it. We want to build this museum From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration. We want people to understand there is this line from slavery to the racial bias and discrimination that we see today that needs to be understood. We want people to come through our museum and walk out with an opportunity to do something. We hope that they’d be prepared to say something that sounds like ‘Never again should we tolerate racial bias and injustice in our country.’”

—BRYAN STEVENSON, founder and executive director, Equal Justice Initiative (APRIL 2017)

Museums’ history of success in addressing hard conversations, in virtual worlds and in real life, has laid the groundwork for their next great work—assisting in the work of truth and reconciliation. The challenge of truth commissions of the past has been confronting the narratives of state violence and other human rights abuses. The TRC recognizes that the social issue of today is the “how” of reconciliation. Because museums have demonstrated their capacity as sites of social action, the TRC taskforce recommended that they receive federal funding to create immersive experiences that, coupled with facilitated dialogue, will create spaces of reconciliation for all people. This funding would help museums build coalitions that emphasize historical clarifications around slavery, genocide against First Nation peoples, and patriarchal narratives. This funding will also encourage museums to challenge American exceptionalist notions that silence the past and present suffering of communities of color.

We have many good examples of the kind of work that can be amplified with this support. The Museum of Impact has grown into an international network of mobile social justice museums. Similarly, the Justice Fleet’s “Radical Forgiveness” exhibition has become a template for audience engagement in museums. The TRC foregrounds dialogue that is led by apology. Reconciliation can only be successful if there is radical forgiveness. Learning from the failures, as well as the successes, of the South African TRC, the USTRC will not attempt to deal with reparations through punitive actions. President-Elect Eaton-Martínez touched on this in her “Mea Culpa “speech: “In order for this country to heal through truth and reconciliation, we must repent of the wrongdoings of the past with a sincere heart of humility … the late Desmond Tutu, one of the founders of the Truth and Reconciliation movement in South Africa said, ‘True reconciliation is never cheap, for it is based on forgiveness, which is costly. Forgiveness in turn depends on repentance, which has to be based on an acknowledgment of what was done wrong, and therefore on disclosure of the truth. You cannot forgive what you do not know.’ We must heal and strengthen ourselves to be able to create a paradigm shift around equity for all people.”

The trust that the president and the TRC task force place in museums as catalysts for dialogue around truth, reconciliation, and healing have solidified these organizations’ role as anchors in our communities. Museums have expanded their capacity to seek the truth and convene discussions while giving agency to those who have not been heard. They have an ability to make connections about cultural similarities and differences in order to transform behavior, removing barriers and organically incentivizing collaboration. Finally, museums have expressed a willingness to share power and decolonize museum practice so that we can all heal and have a true sense of home and belonging.

First published in American Alliance of Museums special magazine edition, Musuem 2040.